Tuataras are among the most evolutionarily distinct creatures in the class Reptilia. Of the four orders of reptiles (Crocodilia, Sphenodontia, Squamata, and Testudines), Sphenodontia (meaning “wedge tooth”), is devoted entirely to the two living species of tuatara, as well as many extinct species. Sphenodonts flourished 200 million years ago and diversified into a wide array of creatures, such as aquatic pleurosaurs.

An illustration of Pleurosaurus goldfussi, a sphenodontian from the late Jurassic that lived in what is now Germany and France.

Tuataras once flourished throughout New Zealand but are now extinct on the main islands. However, ambitious rat eradication programs have reintroduced tuataras to many remote islands off the coast of New Zealand’s main islands.

Tuataras, however, retain the ancient lizard-shaped body plan of tetrapods, though they are only distantly related to squamates, the order of reptiles that includes lizards. They used to be widespread throughout New Zealand; however, their numbers declined with the arrival of Polynesians and then Europeans, who brought cats, dogs, and rats to the islands. Rats in particular have decimated tuataras by eating their eggs, and tuataras can now only live on remote islands off the coast of the main islands of New Zealand.

Special attributes:

- Pronounced parietal eye – Tuataras, like many other chordates, have a parietal eye on the top of their head. Tuataras are distinct, though, in that their “third eye” is relatively well-developed, with a lens and retina. They have, according to Wikipedia, the most pronounced parietal eyes of all extant tetrapods. Their third eyes are only visible as a translucent spot on the top of their heads while they are juveniles; as they mature, pigments and scales cover up the spot. The function of their third eye is unknown; however, it probably plays a role in regulating circadian rhythms and temperature because it is a part of the epithalamus, which controls those processes. It might also manufacture vitamin D.

- Primitive hearing organs – Tuataras (along with turtles) lack ear drums and ear holes, and their middle ear cavity, which in most amniotes (reptiles, birds, and mammals) is filled with fluid, is instead full of adipose (fatty) tissue. They also have primitive middle ear bones and unspecialized hair cells in their inner ear. Because of the simple construction of their ears, they can only hear frequencies from 100-800 Hz, compared to a range of 20Hz to 20,000Hz (20kHz) for humans.

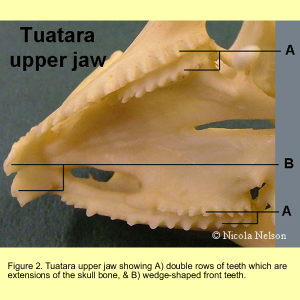

- Funky teeth – Tuataras have two rows of teeth on their upper jaw and one row of teeth on their bottom jaw. The teeth on the bottom jaw fit in between the two upper rows of teeth, allowing tuataras to slice their prey with their teeth. This dental configuration is unique among reptiles; snakes also have two rows of teeth on their upper jaw, but they use them for different purposes. Judging by the information online, the teeth are often said to be extensions of the jaw bone rather than actual teeth. However, Marc Jones informed me in the comments that tuatara teeth are, indeed, real teeth. However, they are fused to the jaw bone and their enamel is very thin. The teeth wear down as the tuatara ages until only smooth jaw bone is left, so old tuataras stick mostly to soft food like worms and grubs.

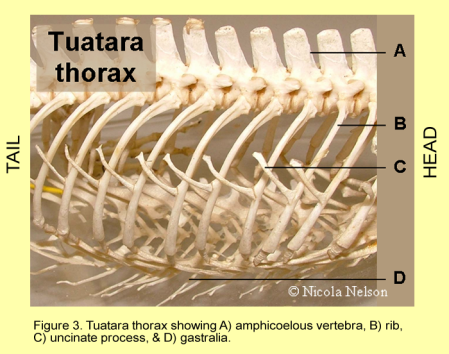

- Ribs – Tuataras are the only tetrapods (a term that includes amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and birds) with well-developed gastralia and uncinate processes. Gastralia are rib-like bones that form a cage on the underside of the abdomen, though they are not actually attached to the spine or ribs. They give tuataras a hard underbelly. The ribs of tuataras are short and have small, hooked projections called uncinate processes, which are present in a less-developed form in birds.

- Miscellaneous traits –

Vertebrae – Tuatara have hourglass shaped (amphicoelous) vertebrae. Though this shape is typical for fish and amphibians, the tuatara is the only amniote (a term that encompasses reptiles, mammals, and birds) known to have such vertebrae.

Eyes – Though not unique to tuataras, their eyes can focus independently and have “duplex retinas” that contain two types of visual cells for day and night vision. Like many other amniotes, they also have a tapetum lucidum, which is a reflective membrane at the back of the eye that enhances night vision, and they have three eyelids – a top one, a bottom one, and a nictitating membrane, which is a clear membrane that moistens and protects the eye while also allowing sight.

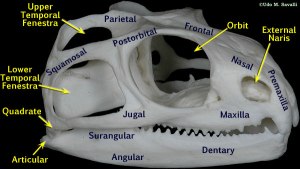

Skull– Tuataras arguably have the most primitive skulls of all the amniotes (turtle skulls might be more primitive), with many of the original amniote features preserved. Most notably, they have two large openings, the temporal fenestrae (meaning “side windows” in Latin), on each side of their skulls [although, as Marc informs me, “The lower temporal bar which forms the lower boundary of the lower temporal fenestra has been secondarily acquired.” So the temporal fenestrae are not inherited directly from primitive amniotes, although they are still a somewhat unique feature of the tuatara].

In the News: You may have heard recently of Henry, a 111-year-old tuatara. For decades Henry was grumpy and aggressive, showing no interest in mating and attacking nearby tuataras. However, in 2002, veterinarians recognized and removed a tumor on Henry’s testicles, and by 2008 he had fertilized Mildred, another tuatara who is probably between 70-80 years old. In a boon to the Southland Museum’s tuatara breeding program, she laid 12 eggs, 11 of which hatched.

Lizard love: 110-year dinosaur descendant to become daddy [CNN] – while I was looking at news article relating to Henry, I found a ton of absolutely incorrect information on almost every web site. This CNN article is ok; however, if you’re interested in tuataras, make sure to stick to dependable sources, not sites like Lalate.com, which reports that “the tuatara is reportedly the only surviving member of the dinosaurs species.”

More Information: I have to admit that I owe a lot (almost everything) on this page to the tuatara Wikipedia article. However, the Wikipedia article draws on a ton of erudite sources for its information, which probably explains why it is so in-depth and technical. So in this case, ironically, Wikipedia is a much more dependable source of information than most of the stuff out there on the web.

Tuatara [Wikipedia]

Unique Features of Tuatara [Victoria University of Wellington]

Sphenodon punctatus [Animal Diversity Web]

Image Sources:

Panaramio – Henry (Sphenodon punctatus) (Image: Oliver Grebenstein)

Wikipedia – Pleurosaurus (Image: unknown, 2008)

Wikipedia – Tuatara (Image: Samsara, 2008)

Victoria University of Wellington – Unique Features of Tuatara (Figure 2) (Image: Nicola Nelson)

Victoria University of Wellington – Unique Features of Tuatara (Figure 3) (Image: Nicola Nelson)

Victoria University of Wellinogton – Unique Features of Tuatara (Figure 1) (Image: Nicola Nelson)

MSN – Move species to save them as Earth warms? (Image: Tim Wimborne, Reuters)

Tags: 111-year-old father, abdominal ribs, ancient amniote, bony teeth, gastralia, henry, parietal eye, pleurosaurus, sphenodon, temporal fenestrae, third eye, tuatara, tuatara misinformation, uncinate processes

December 29, 2009 at 6:43 pm |

[…] (images via: NZ Photo, Wildlife Extra and The Mantis Shrimp) […]

January 25, 2011 at 10:36 am |

[…] skull.https://mantisshrimp.wordpress.com/2009/03/15/tuatara-most-primitive-reptile/ […]

March 18, 2011 at 5:57 pm |

I’m afraid your page on tuatara is littered with myths and outdated half-truths. I wouldn’t trust everything you read on Wikipedia.

For example, Sphenodon certainly does possess real teeth and this has been known for over a hundred years (e.g. Howes and Swinnerton 1901; Kieser et al. 2009). Histological examination shows they they do possess enamel (although thin), dentine, and pulp cavities. What causes confusion is that the teeth are fused onto the jaw bone so that the boundary between tooth and jaw bone is very difficult to discern but there ARE teeth nonetheless (Jones et al. 2009). This is a specialised feature and certainly not primitive (Whiteside 1986; Jones 2008). Also the statement “tuataras possibly have the most primitive skulls of all the amniotes (turtle skulls might be more primitive), with all the original amniote features preserved.” is also not helpful. The lower temporal bar which forms the lower boundary of the lower temporal fenestra has been secondarily acquired. This has been known for 25 years (Whiteside 1986; Evans 2003; Jones 2008) but text books and websites constantly overlooked it for some bizzare reason. Moreover, Sphenodon possess a number of specialised features which you completely ignore including a complex arrangement of tooth rows and sophisticated shearing system (Evans 1980; Whiteside 1986; Evans 2003; Jones 2008; Jones et al. 2009).

# Evans E 1980. The skull of a new eosuchian reptile from the Lower Jurassic of South Wales. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 70: 203–264.

# Evans SE. 2003. At the feet of the dinosaurs: the origin, evolution and early diversification of squamate reptiles (Lepidosauria: Diapsida). Biological Reviews, Cambridge 78: 513–551. DOI: 10.1017/S1464793103006134

# Howes GB, Swinnerton HH. 1901. On the development

of the skeleton of the Tuatara, Sphenodon punctatus; with remarks on the egg, on the hatchling, and on the hatched young. Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 16:1-86.

# Jones MEH. 2008. Skull shape and feeding strategy in Sphenodon and other Rhynchocephalia (Diapsida: Lepidosauria). Journal of Morphology. 269: 945–966. DOI: 10.1002/jmor.10634

# Jones MEH, Curtis N, O’Higgins P, Fagan M, Evans SE. 2009. Head and neck muscles associated with feeding in Sphenodon (Reptilia: Lepidsauria: Rhynchocephalia). Palaeontologia Electronica 12 (2, 7A): 1–56.

# Kieser JA, Tkatchenko T, Dean MC, Jones MEH, Duncan W, Nelson NJ. 2009. Microstructure of dental hard tissue and bone in the tuatara dentary, Sphenodon punctatus (Diapsida: Lepidosauria: Rhynchocephalia). In Koppe T, Meyer G, Alt KW, eds. Interdisciplinary Dental Morphology, Frontiers of Oral Biology (vol 13). Griefswald, Germany; Karger. 80-85.

# Whiteside DI. 1986. The head skeleton of the Rhaetian sphenodontid Diphydontosaurus avonis gen. et sp. nov., and the modernising of a living fossil. Phil Trans R Soc London B312:379–430

August 12, 2012 at 6:52 am |

Hey Marc,

Thanks for the info. I have to admit that I’m no expert at this stuff, I just think these things are cool. I’ll take your word that the things you’re telling me are correct and update my post, since I’d love to help break the chain of misinformation that’s apparently on the net right now.

August 23, 2012 at 9:48 am

No worries. Sorry if I seemed a harsh on some of the previous text but its great you are open to feedback and the figures look really good. Here are some more papers in case you are interested:

# Curtis N, Jones MEH, Shi J, O’Higgins P, Evans SE, Fagan MJ. 2011. Functional relationship between skull form and feeding mechanics in Sphenodon, and implications for diapsid skull development. PLoS ONE 6(12): e29804. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0

# Jones MEH, O’Higgins P, Fagan M, Evans SE, Curtis N. 2012. Shearing mechanics and the influence of a flexible symphysis during oral food processing in Sphenodon (Lepidosauria: Rhynchocephalia). The Anatomical Record 295: 1075-1091. DOI 10.1002/ar.22487

# Meloro C, Jones MEH. In press. Tooth and cranial disparity in the fossil relatives of Sphenodon (Rhynchocephalia) dispute the persistent ‘living fossil’ label. Journal of Evolutionary Biology DOI: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2012.02595.x

October 23, 2011 at 5:42 pm |

about…

[…]Tuatara – The Most Primitive Reptile « The Mantis Shrimp[…]…